Reproduz-se na íntegra o texto publicado ontem por Matt 0'Brien no The Washington Post, dada a análise extensa e factual sobre a situação na Grécia e na União Monetária.

By Matt O'Brien July 13 at 9:38 AM

Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, center, speaks with Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, left, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel. (Geert Vanden Wijngaert/AP)

There's a deal, and it seems Greece won't be leaving the euro zone, at least any time soon.

In the end, Europe's wealthy powers decided to grant Greece a new lifeline in exchange for new budget-cutting and tax-hiking measures, and Greece is slated to avoid a sudden banking collapse that would probably have forced it out of the 15-year-old currency pact.

In the end, Europe's wealthy powers decided to grant Greece a new lifeline in exchange for new budget-cutting and tax-hiking measures, and Greece is slated to avoid a sudden banking collapse that would probably have forced it out of the 15-year-old currency pact.

The agreement in Brussels on Monday probably avoids not only an economy-crushing event but also a major reversal for 60 years of increasing European unity. But the story is far from over, with Greece in line for years of economic adjustment (read: pain), and many new doubts about the long-term potential of the euro zone and its capacity to turn the continent into the United States of Europe.

Here are the basics of what's happening, how we got here, and what it means for Greece, Europe and the rest of the global economy.

1. What's the situation right now?

After a marathon negotiating session, Europe's leaders came to an agreement on a deal to continue financial assistance to Greece in exchange for significant concessions. It's a complicated, and still somewhat tenuous, accord.

What Greece must do

- By Wednesday, Greece's ruling party, Syriza, must pass a host of policy changes as a show of good faith. Those include cuts to public pensions and sales tax increases demanded by Europe to increase Greek budget surpluses.

- Then, over the following days and weeks, it must take other steps to modernize its economy, such as introducing fresh competition to a host of industries from bakeries to drug stores, privatization of the state's power company and changes to labor laws that would would loosen the power of labor unions and make it easier for companies to fire workers.

- Greece must also contribute 50 billion euros of privatized assets -- such as state-owned companies -- to a fund that will help Greece pay off its debt. A quarter of this fund could be used as a domestic economic stimulus, which could grow the economy and generate additional raise tax revenues for debt repayment. (1 euro buys $1.11.)

What Europe will do

- In coming days, Europe will advance a loan of 10 billion euros to help Greece make a 3.5 billion euro payment due to the International Monetary Fund on July 20 and keep its banking system alive. Germany will vote on the agreement as soon as Friday

- This is not part of the formal agreement, but it's widely assumed that the European Central Bank, which has been funding Greek banks with emergency loans, will continue that help in light of the deal

- After Greece passes initial reforms, Greece will receive up to 77 billion more euros over three years. About a third of that will be used to strengthen its banking system, which has been shut down for two weeks amid rapidly declining deposits.

- Europe will also commit to review Greece's total debt burden, potentially giving the country more time to pay it back. But Greece will not get the reduction in face value of the debt that it has asked for.

The risks ahead

The main dangers ahead appear to be political. The latest round of the crisis, after all, began after Greece elected Syriza, an anti-austerity party, to form the government. It is possible that domestic political upheaval in Greece could, in coming days or months, unravel the agreement with Europe. And given that Greece is now likely to undergo a period of long economic pain, that might increase the risk of political instability.

More immediately, the process for reopening the banks or easing capital controls, which prevented Greeks from moving money offshore, still needs to be worked out.

But for now, the euro zone stays intact.

2. What led to the deal?

The deal is virtually the same one that Greece's leadership rejected two weeks ago, that Greece's voters rejected one week ago -- except that it is harsher in places, such as the establishment of the asset fund to pay off debt.

Two weeks ago, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, the leader of Syriza, broke off negotiations over a similar European offer of fresh financial assistance in exchange for tough new austerity measures, and called a referendum on it instead. Europe's leaders weren't exactly pleased, and they insisted that voting against the bailout would mean voting to leave the euro zone. Despite this, Tsipras campaigned against the deal, because he said rejecting it would give him the bargaining power to get better terms — and he unexpectedly won in a landslide.

It was an empty victory. Tsipras had just as much leverage after the referendum as he had before it: none. Athens had already had to close Greece's banks when the European Central Bank refused to provide more of the emergency loans that they rely on to stay afloat, in light of the referendum. The economy began to shut down. Tsipras had no choice but to comply with Europe's demands if he wanted to keep Greece in the euro — which he, and the Greek people, did. That's why Athens capitulated a few days later and proposed almost the same bailout that it and the voters had just turned down. The Greek parliament quickly ratified this surrender.

But even though Greece was now willing to meet Europe's old terms, that wasn't enough. The sticking points had been how fast Athens would phase in pension cuts for poor Greeks and how high the sales tax would be at the country's island hotels. Greece quickly yielded on most of these points. The big problem was that Greece had destroyed its credibility with Europe, particularly the Germans. Europe didn't trust Syriza and didn't want to deal with them.

And for a time, it looked like there would be no deal. Germany had circulated to other countries a plan to force Greece to take a five-year "time-out" from the euro, and Finland had said it couldn't sign off on a deal or its anti-bailout government would collapse. But ultimately, blowback from other countries wanting an end to the crisis, including France and Italy -- as well as pressure from the United States -- gave momentum to those favoring a deal.

In the end, Europe couldn't quite demand that Greece expel its democratically elected government. So it decided it had to stiffen the cost of assistance and require that Syriza prove it could pass reforms first.

3. What was at stake here?

The numbers were never really key here. The ultimate bailout represents only a fraction of a percentage of the total economic output of the euro zone.

The debt was never really the big issue here. Greece is never going to pay back all its debt, and the International Monetary Fund has said that. Greece's interest rates are so low and it has so long to pay back what it owes that even though its debt is 175 percent of gross domestic product, its debt payments are a much more manageable 2.6 percent of gross domestic product. That's less than the U.S. government's debt payments.

Nor was Greece much of a threat to Europe's economy. Greece's economy is only about 2 percent of the euro zone's total. The ECB has erected a firewall and would do all it can to make sure any financial explosion is contained. Investors in Europe and around the world have had five years to detach from Greece.

So what was behind all this? The best way to think about why something so small still matters so much is to think about how we got here in the first place. Whenever a country borrows too much, the IMF usually recommends that it write down its debts, balance its budget and devalue its currency. The idea is that it's pointless to try to pay back more than you can — it can actually be self-defeating — but you also need to become fiscally self-reliant so you don't have to go back for one bailout after another.

The tricky thing, though, is that at the same time you're raising taxes and cutting spending, which hurts the economy, you need to get it growing again. That's why the IMF prescribes a big dose of monetary stimulus — that is, a cheaper currency — to offset the economic pain from fiscal austerity.

But this isn't what happened in Greece. Well, aside from the austerity. It did get a lot of that. What it didn't get, though, was a cheaper currency or enough debt relief. See, back in 2010, policymakers were petrified that the euro zone was like a line of dominoes just waiting to get knocked over by the weakest link. If Greece defaulted on its debt, the French and German banks that had lent it money might go bust, and the banks that had lent them money might, too. Not only that, but default also might force Greece out of the euro, at which point markets would begin to bet against whatever they thought was the next weakest link. That would push up borrowing costs for, say, Portugal and make it more likely that it would, in fact, default, which would then push up borrowing costs for Spain. In other words, Greece wasn't allowed to default, even though it needed to, because doing so threatened to set off a series of self-fulfilling prophecies that could have ripped the common currency apart.

So Greece got bailed out to the extent that it was given money to then give to the people to whom it owed money. That was good news for French and German banks that got their money back, but it wasn't for Greece. It still had as much debt as before, only now it owed official creditors such as the IMF instead of private ones like the banks. Since 2008, Greece's debt burden has shot up mostly because of its economy getting smaller rather than its debts getting bigger.

The Europeans faced a choice, but the problem was they don't how what they decide will turn out. It was possible that ejecting Greece from the euro could actually make it easier for the rest of the euro zone to come even closer together. Or ejecting it could have been the end of the dream of a United States of Europe. But in either case, the continent's political future was at stake.

In the end, the Europeans decided they weren't willing to give up on the dream.

4. What's next?

Assuming that Syriza passes the reforms, Europe unlocks the aid, the ECB continues funding the Greek banks, and all goes according to plan, things will go back to normal, or what we refer to as normal when a formerly rich country is suffering a Great Depression with 25 percent unemployment.

Syriza would implement the tough austerity it has promised, unless something else goes wrong, which it might, and Greece's economy would suffer for the foreseeable future. Its unemployment rate would stay elevated, and the brain drain of the country's best and brightest would continue.

As this tweet from RBS Economics shows, Greece has suffered one of the worst economic declines in modern history, especially considering that it is not at war.

Greece's GDP collapse is among the worst advanced economy falls since 1870. And most of those were war-related.

Over time, as reforms start to have an impact on the Greek economy and the crisis abates, Greece might start to grow again. That is what happened last year, after all, before the latest round of crisis.

5. What does the deal mean for the European and global economies?

- Europe: Europe avoids substantial losses. Greece's government had previously received 240 billion euros in loans, and the ECB had on the line 89 billion in euros of loans. Much of that could have been lost in a default. The deal also prevents any financial contagion in other weak countries such as Italy, Spain and Portugal. The euro is likely to stay stronger, which actually isn't great for European growth since it weakens export competitiveness.

- The United States and everybody else: We can start worrying about other things like the state of China's economy and whether and by how much the U.S. Federal Reserve hikes rates later this year.

6. What's the history to all this?

As the culmination of Europe's 60-year project toward greater and greater integration, the euro was a political masterstroke. It was also an economic albatross. And it's one that wasn't hard to see coming. Plenty of economists, including Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman, warned that it wouldn't work for countries with different economic needs to share a single monetary policy but not a fiscal policy. At any given time, money would be either be too tight or too loose for some members, and there wouldn't be anything — like unemployment insurance — to balance it out. The euro, in other words, is a paper monument to peace and prosperity that has made the latter impossible for some countries.

None more so than Greece. Its big bubble in the early 2000s was the result of interest rates that were too low for it, and its big bust since is, in large part, the result of a currency that has been too strong. With a stronger economy and much less debt, Germany should have always paid less to borrow. But investors treated more risky Greece and Germany the same for years, because they were both part of the euro.

When the debt crisis started, though, investors abandoned Greece and rushed for safe havens such as Germany (and U.S. Treasury bonds).

Now, instead of being able to devalue its way back to competitiveness, Greece has been forced to deflate its economy. That is, it has had to cut wages — which makes unemployment worse — rather than cut its currency. It's the same problem that the gold standard created during the 1930s.

The charts show why Greece wanted to take control of its own future. It is suffering the worst unemployment on the continent — worse than unemployment in the United States during the Great Depression — and even worse unemployment among its young workers. When they see that one in two young Greeks is unemployed — a problem that will cast a shadow on the Greek economy for generations — Greece's leaders wanted a different course.

The European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund — "the troika" — were giving Greece the money it needed to function and to, well, pay the troika back. The IMF, in particular, insisted that Greece cut its pensions by 1 percent of gross domestic product, and Greece initially responded that it was willing to cut them only half as much and make up the difference with higher taxes on businesses. When they couldn't come to an agreement, Tsipras called for the referendum.

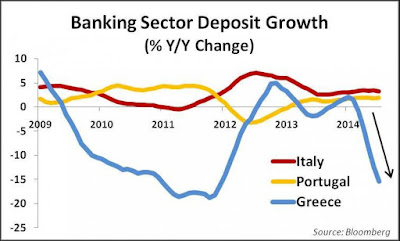

That led to not only a political escalation of the crisis — but an economic one. There has been a slow-motion bank run the past few months — a bank jog, really — that has picked up pace as it has appeared as if there wouldn't be a deal. That's because people were worried that Greece would be forced out of the common currency without one, and their old euros would get turned into new Greek drachmas, which wouldn't be worth anywhere near as much.

So when there wasn't a deal, Greece was forced to close its banks, limit ATM withdrawals to 60 euros a day and prevent people from moving their money abroad in a capitulation to this panic. Then Greece defaulted on a 1.5 billion euro payment to the IMF. That wasn't surprising. Greece didn't have 1.5 billion euros. It didn't have anything. It's broke.

The Washington Post

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário